The term has been widely seen in the media in recent years, and well-known corporations have been accused of greenwashing. How can one tell the difference between greenwashing and green marketing? Here’s how you can recognize it, and what to look for.

Most of the false green marketing claims and greenwashing are associated with two common marketing tactics: branding changes (to make their products and/or packaging look more ‘green’ and eco-friendly), and claims of legitimacy that focus on eco-friendly aspects of the product and purposefully ignore any negative environmental impacts.

Various studies on greenwashing, notably Terrachoice, a division of UL have concluded that up to 95% of consumer products claiming to be green employ some of these greenwashing tactics:

Greenwashing tactics

Hiding & Omission of negative impacts: claiming that a product is ‘green’ based on a narrow set of attributes that ignores other important environmental issues, or highlighting the lesser evil about a product category while omitting the greater environmental impact of the category as a whole (for example, saying that bamboo is more sustainable than cotton, which may be true for the farming aspect of bamboo vs. organic cotton, but omitting the fact that bamboo fabric manufacturing is way more toxic than cotton). Another example of this is H&M cherry picking the information that they got graded A for Climate change actions, but leaving out the other two results of the report: that they got a D for forest management and B for water management. This may also be as simple as incomplete ingredients or fabric components list, claiming responsible manufacturing but failing to mention where or how the products are made.

Lack of proof: making claims that are not substantiated by easily accessible information or by a reliable third-party certification.

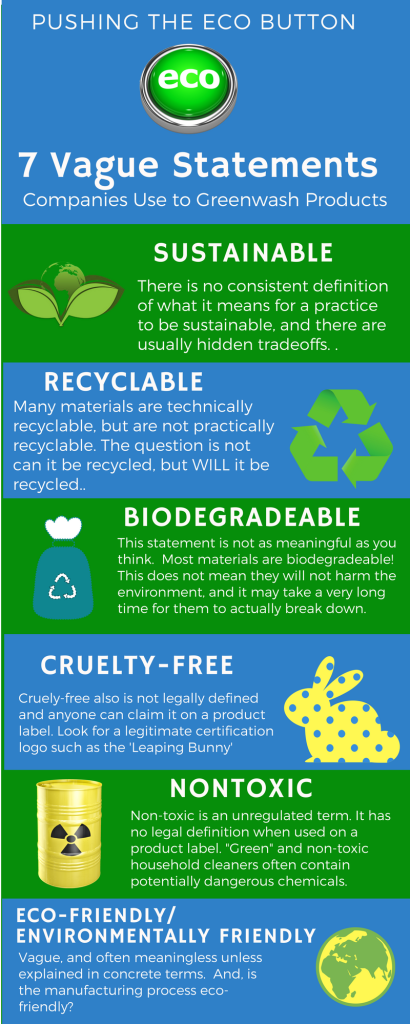

Vague and opaque claims: claims that are so broad and generalized, that their real meaning is easily misunderstood by the consumer: “all-natural” for example does not mean “green” and ‘loving nature’ doesn’t mean a company is involved in any sustainable practices. “Cage-free” eggs are often misleading, because in reality hens aren’t in a cage, just in crowded indoor pens. Even positive terms such as “eco-friendly”,“sustainable”, “responsibly-sourced”, or even “fair trade” on company’s packaging are meaningless and become vague claims without a company providing tangible proof of what their actions.

Fake endorsements or testimonials: claiming through misleading words or images that the products are endorsed by a third party when they’re not. The farmer holding a chicken in a photograph on the label may actually be a paid model, not the actual farmer.

Irrelevant information: highlighting truthful, but unimportant or unhelpful information (like useless statistics, or highlighting the organic shape of a bottle) to mislead consumers seeking an environmentally-conscious product.

False claim: Fabricated data or lie in a claim, often made in a very plausible manner, to seem true. This can also be certifications logos for companies that don’t exist.

Small-print (or asterix): claims that may be true, based on certain conditions, often identified by a superscript or asterix (*) sign with explanatory note at the bottom, in small print, that mentions about the exclusion, but is often missed.

Shift of responsibility: claims about environmental impact of products that may be true, but are based on false assumptions of customer action. For example: fashion companies’ claim of lower CO2 emissions based on consumer actions (washing clothes less, wearing them for longer, recycling) instead of accounting for the CO2 emission of its garment manufacturing and production.

Using mis-matched measurement criteria: two statistics presented in different measurement systems (i.e. metric tonnes vs tonnes) that are misleading as to what they mean.

Social responsibility and donations: companies claiming that they’re taking care of workers by donating a small portion of the sales profits to a charity without specifying how much is donated, mentioning a list of charities they donate to, or vague claims of helping a community or social group without any specific claims to back it up.

Carbon credits: claiming zero-footprint or carbon offsets by purchasing the products is also similar to greenwashing, as it presents products to have a smaller environmental impact than reality: rewarding consumers with carbon offsets without specifying the percentage of their purchases donated to buy carbon offsets, or the way carbon credits are priced or accounted for.

Misleading imagery: when you see the color green (or brown kraft packaging) and images or words related to sustainability (trees, animals, the Earth), take a closer look at the product and company website. If a company doesn’t provide verifiable data backing up its claims, they’re probably engaged in some level of greenwashing.

Packaging: Does the company use recyclable packaging and does it make any effort to ensure its consumers are recycling the packaging or serving-ware?

Greenwashing tactics are very subtle, and practiced by multi-national corporations. Here are some examples of greenwashing that companies have been called out on in recent years.

How to spot greenwashing

The distinction between greenwashing and green marketing is often very blurry and requires a trained eye and additional research to see how companies are backing up the claims in their marketing and advertiing campaigns, and to see if their back-up information is actually true, and not hiding anything else.

Greenwashing tactics are very subtle, and practiced by multi-national corporations. Here are some examples of greenwashing that companies have been called out on in recent years.

Here are some things you can do to spot greenwashing:

1. Check product label & packaging

What words and images are used by the company to signal that they’re eco-friendly and what are they trying to communicate? Are there any certification stamps/symbols on the label? Do they look similar to the certification website? Do they provide additional information on their website or social media to back up their claims? Is the packaging recyclable? Look for tell-tale known terms such as “natural/all-natural”, “organic”, “chemical-free”, “preservative-free”, green labels, imagery of nature (see info-graphic) and other info.

2. Check company website and other information they present to back up their claims

Does the company have ample and detailed information on their website that backs up their claims and provides quantitative information on what they’re doing? Is there transparency between what they say they’re doing and their claims? If there is missing information, or vague and general terms, they’re probably engaged in greenwashing.

3. Look for certifications.

Are they showing any third-party certifications on their product label or website? What does the industry research say about the claims they make, is there validation? Is there any information that was omitted by their claims or incorrect?

4. Do additional industry research to verify claims: Is the industry information backing up their claims? Is there anything they’re leaving out?